MongoDB is so awesome to offer free training at their MongoDB University, so I joined their course “MongoDB for DBAs” or MongoDB for database administrators.

I’m definitely not a database administrator, but their “MongoDB for Node.js Developers”1 doesn’t start until January 13th, 2014… and I just couldn’t wait that long. This article will be the first in a series of articles covering what I learn each week. The first week is an introduction to MongoDB.

You can watch the lectures of week 1 on YouTube.

Concepts and philosophy

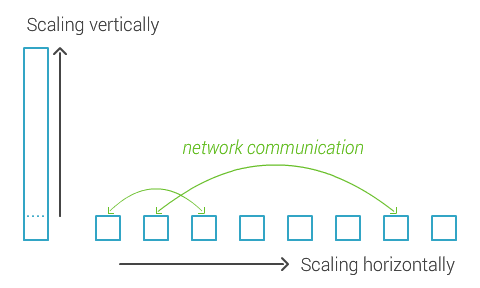

Why would you want to use MongoDB while we have relational databases? One reason could be because relational databases were developed in ancient times and didn’t scale well with modern technology. MongoDB however is designed to work with modern technology. Think about parallelism, lots of cores, networking, lots of servers, cloud computing. Traditional ways to scale an application is to scale vertically, or buy a bigger box

. But big boxes are expensive, and what if there is no bigger box? MongoDB scales horizontally, you just buy more boxes

instead.

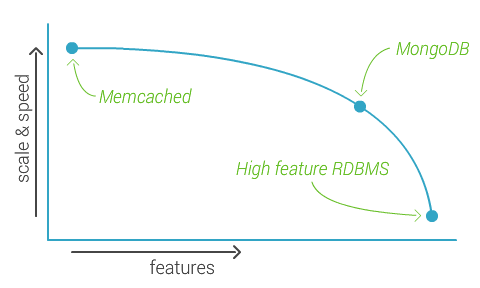

The problem is all those boxes are separate servers and need to communicate over the network, which introduces latency, which makes things slow. MongoDB’s approach is to sacrifice features to keep things manageable and fast, but at the same time keep enough features to do interesting stuff. Take a look at the following graph:

The idea is if a product doesn’t have any features it might scale really well, but if it has lots of features that becomes hard. All the way to the left you might have something like Memcached, and all the way to the right some super high feature RDBMS. The people behind MongoDB observed that this curve is not linear and so they try to push features up till the “knee”, but no further. The result should be a scalable and fast product, while still keeping about 80% of the features.

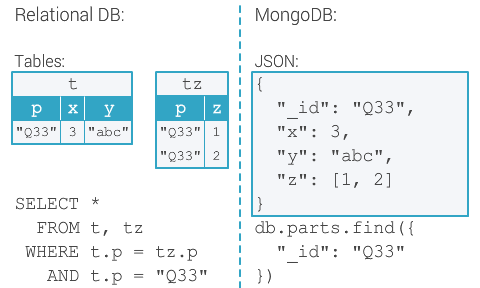

Some of the features that didn’t make it are joins and complex transactions, for which it was too hard to come with a clever solution considering you might have your data distributed across hundreds of servers. Because joins are essential for relational databases, another data model was needed. The approach in MongoDB is a “document-oriented” database, which means documents with some structure.

Another reason to use MongoDB is it makes development easier. These documents are in JSON-style (JavaScript Object Notation) format instead of, for example, XML which is rather complex and hard to read. JSON obviously looks like code because it derives from JavaScript, making it easy to read, but is language independent and there even is a RFC standard for JSON. The philosophy is developers should be able to read documents without reading the program.

Because MongoDB doesn’t have joins, an alternative is to not break up the data. While relational databases have joins, MongoDB has nested or embedded documents which makes querying easier as you can see in the following comparison.

Also, MongoDB is non-structural, as in it doesn’t enforce some database schema making it much easier to support polymorphism in your data. Consider objects that have some common properties and some unique properties, in MongoDB you can store those objects in the same collection.

Installing MongoDB

Installing MongoDB is trivial, download a package from mongodb.org and unpack it. There are some things you should pay attention to though:

- Go with the 64-bit version (if you have a 64-bit machine), otherwise MongoDB will be limited to 2GB of data because it uses memory mapped files.

- By default MongoDB stores data in

/data/db, so you’ll need to create that directory or specify another directory with./mongod --dbpath <directory>. Make sure that directory is writeable, for examplechmod 777for development environment. - You don’t need to install MongoDB, just run the server

./mongodand then the shell client./mongo. The./makes sure you get what you expect and not something set as PATH variable.

To exit a service running in the shell type exit or press Ctrl+C (or probably something similar for Mac).

JSON types and syntax

JSON, or JavaScript Object Notation, is an open standard format that uses human-readable text to transmit data objects consisting of attribute–value pairs. It is used primarily to transmit data between a server and web application, as an alternative to XML.

Although originally derived from the JavaScript scripting language, JSON is a language-independent data format.

MongoDB uses JSON (or rather, BSON, but we’ll get to that) to deal with structured documents. But what is JSON exactly? Take a look at the following simple example:

{

"name": "Dillon",

"age": 31,

"awesome": true

}

If you’re a JavaScript developer, this should look familiar. A JSON document can have one or more key: value pairs. The keys are always strings and must always be quoted (unlike in JavaScript, where quotes are sometimes optional), and the value can be one of the following types:

- Number (double-precision floating-point format, depending on implementation)

- String (double-quoted Unicode, with backslash escaping)

- Boolean (

trueorfalse) - Array (an ordered, comma-separated sequence of values enclosed in square brackets)

- Object (an unordered, comma-separated collection of

key: valuepairs enclosed in curly braces) null(empty)

In MongoDB, an object is called a document.

One final thing to point out is that, in JSON, keys “should” be distinct. The specification doesn’t say “must”, which means duplicate keys are “allowed” technically… but don’t do it. In MongoDB it’s allowed at this point but that may change in the future. It wouldn’t make any sense anyway.

Introduction to BSON

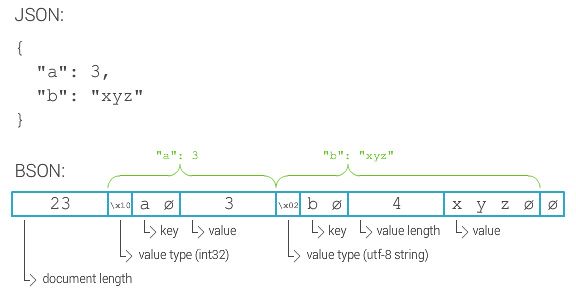

Internally MongoDB stores its data in BSON, or “Binary JSON”, format.2 You don’t really need to know anything about BSON to work with MongoDB so feel free to skip this section but if you’re, like me, wondering about performance and “how stuff works” keep on reading.

Why BSON? One of the reasons is because it’s fast scannable. Considering JSON is just a string, in order to find a specific key you need to scan every single character in that string, keeping track of the level of nesting, until you found that specific key. That could be tons of data that needs to be scanned. BSON, however, stores the length of values so in order to find that specific key you can just skip past values and read the next key.

As you can see in the image, a BSON document starts with the document length, in this case 23 bytes. Lengths are stored as 32-bit integers, little endian, so “23” would actually be stored as \x17\x00\x00\x00. While for readability I wrote “23”, note lengths are 4 bytes long since they are 32-bit integers. Then for each key: value pair BSON specifies the value type as a single byte, key as null terminated string, value length as 32-bit integer if applicable and the value itself. Documents, arrays and strings are null terminated. For arrays I believe indexes are stored as well.

In addition to fast scannability, another reason are the additional data types in BSON. Most importantly the Date and the Binary type but another, less critical but often used data type is the ObjectId type.

So BSON is used internally in MongoDB, but in addition is used beyond that. Imagine a document in BSON on a MongoDB server, if a client queries for that document, the server will send the BSON document back to the client unchanged though decorated with a header. It’s the driver’s responsibility to transform that BSON document into a programming language specific representation.

The Mongo shell

I think that’s enough theory for a while, let’s get our feet wet.

To be able to use the Mongo shell we first need to have a MongoDB server running in another shell. We can start the MongoDB server with the default dbpath (/data/db), or specify another directory to use:

./mongod

./mongod --dbpath <directory>

If you get an error it’s probably because the directory doesn’t exist. MongoDB won’t create it for you.

Now we can start the Mongo shell with:

./mongo localhost/test

Making it connect to the MongoDB server running on localhost on port 27017 (default) and use the database named “test”. Actually all of that is default and optional.

We can show all databases and their sizes, switch database and show the current database using the following helpers:

> show dbs

> use test

> db

A database consists of collections, this helper shows all collections in the current database:

> show collections

Collections (of documents) are usually created implicitly when you insert a document. To insert a document to the collection “foo” and query for all documents we can use these methods:

> db.foo.insert({"hello": "world"})

> db.foo.find()

You’ll notice MongoDB assigned an _id key to your document, this is the primary key and can be any data type as long as it’s unique. If not specified, MongoDB will assign a key of type ObjectId.

When the collection gets larger, and your query returns a lot of unreadable mess you can make it more readable using:

> db.foo.find().pretty()

Ain’t it pretty! There are a lot more helpers and methods, see for yourself:

> help

If needed, you can use the import utility to import data into MongoDB. You can import CSV, TSV or JSON data.

./mongoimport --db <database> --collection <collection> --file <file>

Specifying database name, collection name and path to the data file. Let’s do that right now. Download products.json and then import (in another shell or exit Mongo shell first) that file in collection “products” from database “pcat”.

./mongoimport --db pcat --collection products --file /path/to/products.json

Let’s see if that worked. Go back to the Mongo shell and type:

> use pcat

> db.products.count() // 11

> db.products.find() // unreadable mess

> db.products.find().pretty()

Pretty right?

Queries and sorting

Week 2 will be all about CRUD (Create Read Update Delete) operations so this is just a preview. Now we have our products collection we can practise some queries on that. The find() method accepts two parameters, a criteria object and a projection object. The criteria object contains query parameters (comparable with WHERE in relational databases) and the projection object contains fields that we want to return (comparable with SELECT). Run the following queries:

> db.products.find({"price": 12}).pretty()

> db.products.find({"price": 12, "color": "green"}).pretty()

> db.products.find({"price": {"$gte": 200}}).pretty()

> db.products.find({"price": 12}, {"name": 1})

> db.products.find({"price": 12}, {"name": 1, "_id": 0})

> db.products.find({"type": "case"}, {"type": 1}).pretty()

> db.products.find({"limits.data.n": "unlimited"}, {"limits": 1}).pretty()

There are a couple of things to notice here:

- If you specify more than one field criteria all of them must match.

- There are special

$operators, like$gte(greater than or equal).3 - The

_idfield always gets returned, unless explicitly set to0. - To reach into an array you don’t need to do anything special, MongoDB is smart.

- To reach into an object you need to use dots

.between fields.

To sort documents we can use the sort() method after the find() method. It takes a parameter in the form {field: direction} where direction can be 1 for ascending or -1 for descending. Let’s try that:

> db.products.find({}, {"price": 1}).sort({"price": 1}).pretty()

That query returned all 11 documents, even though some of them don’t have the “price” field. That’s because in MongoDB, there is a sort order between types, for example null is lower than any Number and any Number is lower than any String. If a document doesn’t have a field, that value is considered null, which is used for sorting.

MongoDB uses indexes (if there is an index) for efficient sorting.

Speaking of efficiency, there is one last implementation detail I would like to mention. MongoDB is lazy. For example, if you have a collection with 20000 documents and query for them all, the server will send back a reasonable sized batch until you ask for more.

> for (var x = 0; x < 20000; x++) db.test.insert({"x": x})

> db.test.find()

> db.test.find({"x": 1337}).explain()

> db.test.find().skip(10000).limit(10)

In fact, MongoDB is so lazy that if you assign a query to a variable, that query doesn’t run until it’s evaluated.

> var query = db.test.find()

> query // now the query runs

Final notes:

- When you send a query to the MongoDB server you get back a cursor.

- Only when the query is evaluated MongoDB runs the query, sending back reasonable sized batches. You can get the next batch using the command

getMore, or type “it” (iterate or something) in the Mongo shell. - Querying for a field that’s not indexed is expensive, MongoDB needs to look at every document in the collection.

skip()is expensive too.

That’s it for this week, see you next week!

-

Get MongoDB certified with free online training at MongoDB University. ↩

-

Learn more about BSON on bsonspec.org. ↩

-

List of all

$operators is available on docs.mongodb.org. ↩