Why would you want to parse emoji Unicode in JavaScript? Say you have an application that accepts Unicode (including emoji) as user input, for example for comments or chatting. Most mobile devices have no problem displaying emoji natively, but what if emoji is not supported? Wouldn’t it be nice if you can store the correct standardized Unicode character in your database, and use JavaScript to replace this character with some element that displays an image fallback when emoji isn’t supported?

Detect native emoji support

Since emoji is stored as Unicode characters,1 if emoji is supported natively you don’t need to do anything! Unless you have a custom set of emoji you want to use instead of the operating systems default, of course. Let’s assume you want to use the default emoji, for performance if nothing else. Then you need to be able to detect whether or not emoji is supported. If you’re using Modernizr2, it’s as easy as adding emoji from non-core detects. If you aren’t, you can just take the code to test for emoji support:

var emojiSupported = (function() {

var node = document.createElement('canvas');

if (!node.getContext || !node.getContext('2d') ||

typeof node.getContext('2d').fillText !== 'function')

return false;

var ctx = node.getContext('2d');

ctx.textBaseline = 'top';

ctx.font = '32px Arial';

ctx.fillText('\ud83d\ude03', 0, 0);

return ctx.getImageData(16, 16, 1, 1).data[0] !== 0;

})();

As you can see this test depends on canvas support, which is something we have to live with. You can also see we write the string \ud83d\ude03, which is actually just one Unicode character for the “smiling face with open mouth” emoji. That could be a hint to the solution you’ll later in this post.

What you would expect to work, except it doesn’t

For simplicity, let’s focus only on the emoticon range of emoji Unicode, U+1F600 to U+1F64F.3 Let’s assume some HTML element el containing emoji characters in this range. To replace the characters with a fallback element you would expect this RegExp4 replacement to work:

el.innerHTML =

el.innerHTML.replace(/[\u1f600-\u1f64f]/g, '<span class="emoji" data-emoji="$&"></span>');

Styling the fallback element will be explained later.

Sadly, this doesn’t work. The reason is JavaScript defines strings as sequences of UTF-16 code units, not as sequences of characters or code points.5 This is fine for characters in the Basic Multilingual Plane (BMP), or Unicode range of U+0000 to U+FFFF, but for characters outside this range, in Supplementary Planes (note emoticons starting at U+1F600), two code units are necessary. We will go into the details of how these so called “surrogate pairs” work later, for now let’s go straight to the workaround.

A RegExp that works with surrogate pairs

To create a working RegExp you have to find the surrogate pairs you’re dealing with. Luckily we can easily define a function to do that for us, based on the String.fromCodePoint polyfill.6

function findSurrogatePair(point) {

// assumes point > 0xffff

var offset = point - 0x10000,

lead = 0xd800 + (offset >> 10),

trail = 0xdc00 + (offset & 0x3ff);

return [lead.toString(16), trail.toString(16)];

}

// find pair for U+1F600

findSurrogatePair(0x1f600); // ["d83d", "de00"]

// find pair for U+1F64F

findSurrogatePair(0x1f64f); // ["d83d", "de4f"]

The lead surrogate is \ud83d and the trail surrogate in the range \ude00 to \ude4f. Now you can adapt the RegExp to check for both code units like this:

el.innerHTML =

el.innerHTML.replace(/\ud83d[\ude00-\ude4f]/g, '<span class="emoji" data-emoji="$&"></span>');

And it works!

What about the full range of emoji Unicode?

Until now we’ve only considered emoji in the emoticon range, but what if you want to support the full range of emoji Unicode? There are the “Miscellaneous Symbols and Pictographs” ranging from U+1F300 to U+1F5FF, followed by the “Emoticons” from U+1F600 to U+1F64F. Then there is a gap for some reason and then there are the “Transport and Map Symbols” from U+1F680 to U+1F6FF. Not all of those are actual emoji characters yet, but they are reserved to be so… whatever. There are also some “Miscellaneous Symbols” in the BMP, ranging from U+2600 to U+26FF.

Starting with the long range of U+1F300 to U+1F5FF, we find the surrogate pairs like this:

// find pair for U+1F300

findSurrogatePair(0x1f300); // ["d83c", "df00"]

// find pair for U+1F5FF

findSurrogatePair(0x1f5ff); // ["d83d", "ddff"]

Because the lead surrogate varies over this range you have to be extra careful how to match all the characters in between. Now is a good time to learn how surrogate pairs work.

UTF-16 surrogate pairs

As mentioned before, in JavaScript, strings are defined as sequences of UTF-16 code units. As you might have guessed those are 16 bit each, or 4 hexadecimal digits, so it’s possible to map code points from U+0000 to U+FFFF. That’s just one plane of the Unicode space. There are 16 other planes, each containing the same amount of code points, making Unicode range from U+0000 to U+10FFFF.

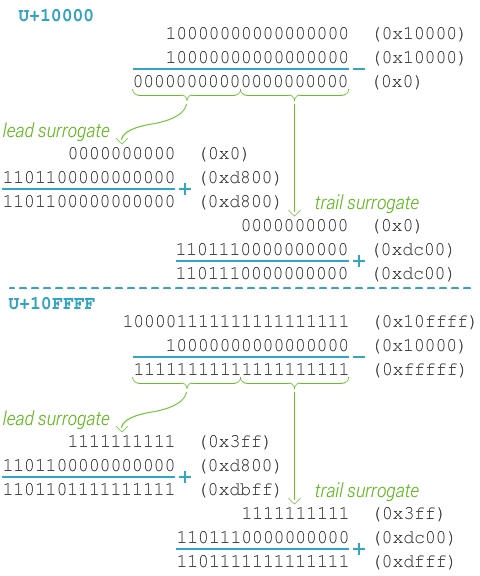

Code points above U+FFFF need to be encoded in UTF-16, but the encoding is simple.7

- Subtract

0x10000from the code point in the rangeU+10000toU+10FFFF, which gives a 20 bit “offset” between0and0xfffff. - Add

0xd800to the high ten bits of the offset (or,offset >> 10), this prepends six bits110110indicating this is a lead surrogate. - Add

0xdc00to the low ten bits of the offset (or,offset & 0x3ff), this prepends six bits110111indicating this is a trail surrogate.

Does any of that rings a bell? Let’s try that with the lowest and the highest relevant code points:

U+10000 is encoded as \ud800\udc00 and U+10FFFF is encoded as \udbff\udfff.As you can see in this image the lead surrogate ranges from \ud800 to \udbff and the trail surrogate ranges from \udc00 to \udfff. This range is important because we use it to match characters in long surrogate pair ranges. Any code point between U+1F300 and U+1F5FF will be represented by either a lead surrogate \ud83c followed by a trail surrogate between \udf00 and \udfff (highest trail surrogate), or a lead surrogate \ud83d followed by a trail surrogate between \udc00 (lowest trail surrogate) and \uddff. That’s for “Miscellaneous Symbols and Pictographs”, similarly we can match all emoji ranges with:

var ranges = [

'\ud83c[\udf00-\udfff]', // U+1F300 to U+1F3FF

'\ud83d[\udc00-\ude4f]', // U+1F400 to U+1F64F

'\ud83d[\ude80-\udeff]' // U+1F680 to U+1F6FF

];

el.innerHTML = el.innerHTML.replace(

new RegExp(ranges.join('|'), 'g'),

'<span class="emoji" data-emoji="$&"></span>');

The array is just to keep everything nice and readable.

I should probably mention there are non-standardized, legacy emoji encodings as well, but dealing with them is outside the scope of this article. See the Emoji page on Wikipedia.

If you’re wondering how to encode code points from U+D800 to U+DFFF, you can’t. They are reserved for lead and trail surrogates and can’t be encoded in any UTF form according to the Unicode standard.

Styling the fallback element

Okay, so now we have replaced every emoji with this HTML element:

<span class="emoji" data-emoji="_"></span>

The only thing left to do is some styling:

.emoji {

overflow: hidden;

display: inline-block;

width: 1em;

height: 1em;

margin: 0 0.1em;

background-size: 100% 100%;

}

/* for each emoji */

[data-emoji="_"] {

background-image: url('path/to/emoji.svg');

}

Replacing the _ with each of the emoji characters you want to support. You can also use code points in CSS, for example [data-emoji="\1f601"], to make it more readable. I’ll leave the details of styling individual emoji up to you. The possibilities are endless after all. Think about PNG or SVG, maybe both for fallback? Single images, sprite map or icon fonts? If you come up with something clever, let me know! Thanks for reading.

-

Your database may not support emoji Unicode yet, if you’re using MySQL for example. ↩

-

List of emoji Unicode ranges, and legacy encodings on Wikipedia. ↩

-

If you’re new to Regular Expressions, check this awesome guide on MDN. ↩

-

Unicode Character Classes in ECMAScript Regular Expressions. ↩